- Â

å September 2015

í Unit 2: Overview & Assignment

Andy Goldsworthy, Storm King Sculpture Park

I suspect no landscape, vernacular or otherwise, can be comprehended

unless we perceive it as an organization of space; unless we ask ourselves

who owns or uses the spaces, how they were created, and how they change.

—John Brinkerhoff Jackson

Preface:

Although graphic design exists in a multitude of spaces, places, and surfaces, it is too often seen as a two-dimensional enterprise. But in fact our work is entirely multi-dimensional. Not only do we design places, wayfinding systems, and exhibits, we also design information environments, complex digital networks, and social interfaces. Moreover, what we produce exists in real time, and real space, used by real people in all dimensions. Designers are experts at reading signs and signals within any situation, large or small. We analyze and record given characteristics, and intervene to change or improve upon circumstances. Design is nearly always engaged with altering, or re-organizing, or improving upon, a given circumstance or set of circumstances, whether at a macro or micro scale.

Lawrence Weiner

Assumptions:

Humans are hard-wired to read signs and signals in any given situation. As we move through our environments, we intuitively and unconsciously look for comfort, safety, and elements that are of value or pertain to us. We avoid danger and discomfort. We are egocentric, but we are also intelligent and quick to read our surroundings. We “read” all manner of spatial form, color, tone, temperature, sensation, sounds, and any number of other characteristics of a place almost instantaneously. We are extremely perceptive and are inclined to find meaning in most things. In this Unit, we will be looking at how we “read” spaces and places, and we will explore how we might intervene upon existing spaces. Our interventions will be a form of discovery — a process for understanding contrasts, narrative, form, and the human desire to form interpretations. As we work for the next two weeks, we will discuss in our sections how we define place; how a place relates to its surroundings; how we embrace the culture of a place, large or small, or how we might subvert its histories and realities.

Jessica Greenfield, RISD MFA alum

Unit Question: How can you alter an existing space (site)?

Additional questions:

-How can you truly “know” a place?

-By altering a site, can you create a new narrative read of the site?

-How does the way you approach the alteration, and the way you frame your documentation of the intervention, affect the “read” of your site.

-How can you document, sequence, and explain your site interventions to create a narrative out of the documentation?

Deliverables:

A designed sequence/presentation (media is open) of your documentation that explains your sites and your alterations to a public audience (us).

Learning Objectives:

1) Getting to know your city and environs.

2) Develop a consciousness about how we define space, place, site, landscape, culture, audience, community

3) Exploration of how formal elements work together, whether in contrast or concord; harmony or discord.

4) Developing resourcefulness around finding unusual and surprising materials or objects to bring to a site for the creation of a new or alternative “read.”

5) Developing an awareness of the power of the artifact/after-the-fact documentation. “How to tell a story for those who werent there.”

Procedure:

- You must choose two sites.

One must be an intentionally built / urban / public / site. Outdoors.

One must be a natural (relatively unbuilt or naturally occurring) environment.

(for example, the RISD’s Tillinghast farm, or (walking distance) Swan Point Cemetery’s woods, or Lincoln Woods State Park, or Weetamoo Woods in Tiverton.) - You must deliberately and attentively get to know your two sites. You should record all manner of characteristics pertaining to your sites. Using photography and other recording techniques, take note of the site’s characteristics, forms, materials, textures, sensations, light, uses, users, sounds, temperatures, intentions. You can also consider cultures, histories, stories, pasts, futures. What was the site. Does it have a past? A future? What can it be? Get to know these two places thoroughly. Think Macro and Micro. Record context and adjacencies. Record edges and boundaries. Record before and after your alterations.

Pay attention to how you frame your recordings/images. How you light or edit your images. How will your technique affect the way an audience might understand your site’s inherent narrative. Show us how you want us to see the site. Show us how the site communicates.

Before the next class meeting you must alter your two spaces in the following ways, and create carefully considered documentary images and recordings:

A.

Transform or intervene upon an existing, built, urban space/place

1) Intervene with color (material is open)

2) Intervene with multiples (more than 25)

3) Intervene with something singular

4) Intervene with language / text / type

B.

Transform or intervene upon a natural space/place:

1) Intervene with language or color or multiples or other items you bring to the place

2) Intervene only with things that you find at the site

RECORD EVERYTHING (photo, video, sound, drawing)

C.

Design your Documentation

for 10/6/15

Bring to class a multitude of images and evidentiary records/documents and begin building a sequential narrative that can communicate to those who were not there exactly what took place; what they might find there if they could be there. Media is open but the sequence of your narrative and how you show a visual flow is to be considered.

for 10/13/15

Bring in refined presentations of your interventions in a narrative sequence of images and texts as needed. These need to resonate with your audience (all of us) in a public viewing, and help us understand the whole sequence of your space alterations.

Required Reading:

Lucy Lippard Lure of the Local

Brief overview of Maya Lin’s work Here

Resources:

RISD Second Life

Resources/Recycling for RI Education

w RI Resource/Recycling Center (ie weird free stuff and lots of it) September 24, 2015

w Helpful List of Formats, Process and Concepts September 24, 2015

í DS1 Reflective Notes

Reflective Tasks

Tom O’s: notes for regular “reflective” practice

Write Daily/ Weekly Reflective Notes:

Knowing (learning) evolves from a dynamic interplay between experience and reflection.

Reflection deepens awareness and insight.

Therefore, make it a daily practice to nurture reflective practice via written notes on your course (this one or others) work and readings: your curiosities, interests, questions for inquiry, delights, challenges, observations, experiences.

Create a quiet moment (if only for a few minutes!), for to act from a quiet mind fosters true insight.

Write spontaneously.

Write, but also feel free to add visual notes, as needed.

Savor this experience of insight.

ALSO: each week share one or more of your reflective notes on work for this course,

via our course blog, and with your section faculty via email!.

Sharing your “insights” allows us (faculty) to be more informed of you:

your interests, thinking and processing of ideas.

Meant as “nothing to prove” but as evidence of your attention to your work, don’t expect a response/critique.

Don’t belabor the task (this is not an English class, not a thesis, not a test!).

Keep writing effortless and simple, in topic and style.

No need to impress anyone with excessive facts or knowledge.

Use any writing style that feels comfortable and natural to you.

Simply practice this reflective mode with sincerity.

NOTE: This practice will also help you toward the final course requirement,

which is to create a Reflective Process Book about your work and what you learned in this course.

í Unit 1: Due week 3

In your group meetings today, you should have honed in on the most striking observations and/or recordings. For next week, focus your attention on a singular curiosity and create five forms (but not necessarily objective) that communicates the value of your attention in that area.

B Unit 1: Readings

Required

“Attention,” Lorraine Daston. Curiosity and Method: Ten Years of Cabinet Magazine

“An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris,” Georges Perec

“Approaches to What?” Georges Perec

“The Rules of the Game,” Paul Auster and Sophie Calle

Supplementary

Video clip from “Smoke” adapted from Paul Auster short story

Interview with Katerina Seda

The Everyday, WhiteChapel Documents of Contemporary Art

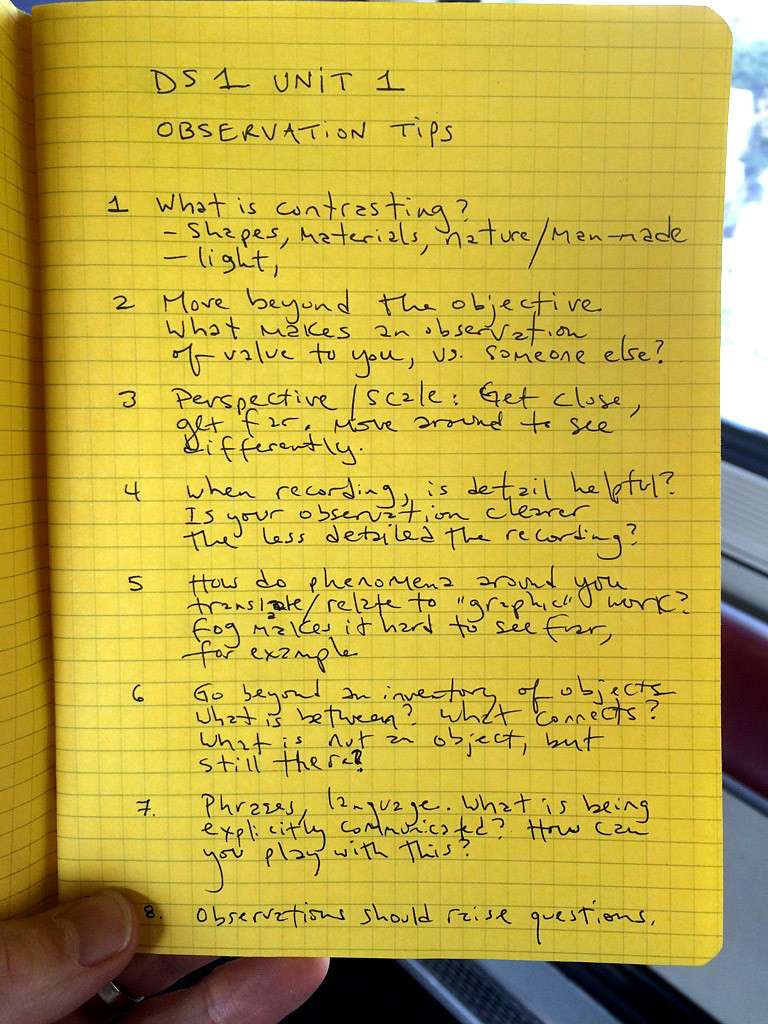

í Unit 1: Day 1, In-class

The Bohemian Dinner, Charles Greene Shaw

Head out to the Independence Trail. Choose a spot and through close looking and careful observation, make as long of a list as possible that describes what you see. What are all the ways you can describe both big and small, natural and man-made, temporary and permanent, boring and extraordinary? At what point do your observations depart from what is objectively there to associations/opinions from the point of view of the maker. Make note of those as well.

Come back before the end of class. If there’s time, split into groups of 3 or 4 and read through/share your lists. Make sure you choose a spot and start.

Your text document should take the form of a hand-written list on letter-sized paper so that it can be share with your groupmates and pushpinned on the wall at the end of class for general class or small group review. The exercise should demonstrate the range of possible observations and start to suggest where value lies in the everyday urban observation. How objective and subjective are the observations, and what ideas arise from any of it? Camera phone your list and place on Google Drive/website (what your instructor suggests) by the end of the unit.

í Unit 1: Due week 2

Pick one spot in the city and begin to think of it as yours. It doesn’t matter where, and it doesn’t matter what. A street corner, a subway entrance, a tree in the park. Go to to your spot every day at the same time. Spend an hour watching everything that happens to it, keeping track of everyone who passes by or stops or does anything there. Take notes, take photographs. Make a record of these daily observations and see if you learn anything about the people, or the place, or yourself.

—‘The Rules of the Game,’ Paul Auster to Sophie Calle

Let’s play by Paul Auster’s rules. Choose one of the 50 spots on Providence’s “Independence Trail” as your spot. The historic significance of the Independence Trail serves as a note of possible contrast with what you will see in today’s Providence, but for the most part, it’s a system of spots.

You are learning to work with what already exists, before you do anything. Using all of the following recording techniques, create an exhaustive amount of documentation of the area surrounding your spot (100 documents minimum). You may move from your spot to record or further inspect, but limit your field of attention to what you can see from the spot you choose from the below map. Note the word exhaustive is meant to force you to deeply engage with your area. Go to your spot a minimum of three times for at least an hour each time. As far as recording, some media may make more sense than others based on what grabs your attention. Notes may work better than images in some places or cases (nighttime). Be sure to spend a good deal of time not recording anything at all. A recording is often the result of seeing not a mediator of what you see. Experiment with all of the following:

- Photography (in all its permuatations)

- Diagrams

- Sketches

- Lists

- Narrative paragraph

- Audio

- Video

- iPhone apps?

Present your findings to your classmates in section at the start of class next week in an organized fashion. Pin up what can be pinned up, have a laptop out for digital assets, make sketches visible, etc. We will look at the results briefly as a group, then work in smaller groups to discuss how well the forms you made are communicating what you saw. Address this line of questioning when you show your work: What did you notice of value? What did you decide to share? How did the way you recorded and shared your observation make sense given what you saw and what you want to say?

Everyone should be set up by the beginning of class.

This first unit is meant to kickstart best practices and ongoing forms that you will use in the next two years. Buy and begin using a sketchbook (letter-sized or smaller), set up a blog (specifically for this class, not Instagram or Pinterest… tumblr is ideal) and begin to reflect and document your experiences in a way that will make your final documentation go smoothly.